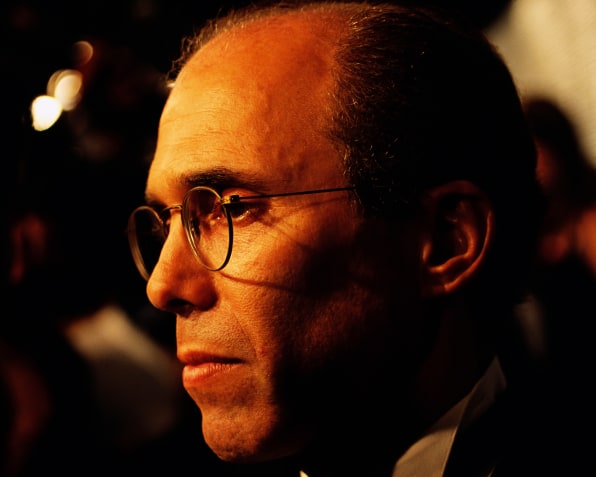

When Jeffrey Katzenberg first announced Quibi, a mobile app that serves up “quick bites” of video made by A-list stars, it was hard not to recall the first time the former Disney honcho pitched a short-form digital video platform promising to transform the way we consume entertainment. Katzenberg, after all, had tried more or less this exact same idea 20 years earlier, in another frothy tech market where abundant capital superseded operational excellence.

That would be Pop.com, an entertainment site dreamed up by Katzenberg and his then partners at DreamWorks SKG (Steven Spielberg and David Geffen), along with Imagine Entertainment partners Ron Howard and Brian Grazer, that promised users short “pops” of streaming video. It was something of a revolutionary concept, given the era in which it was conceived—more than two decades ago, at the height of the dot-com boom, and five years before YouTube. It was also an enormous risk, given that most people in 2000 did not have broadband internet and almost all digital media consumption was on desktop computers. Internet video was still a clunky, time-consuming affair.

Undeterred, Katzenberg and Co. plowed ahead with a showy launch party at the Chateau Marmont, headline-making deals with stars, an enormous payroll, and promises to rewrite the rules. There was never anything hesitant or iterative about Pop. In keeping with the ethos of DreamWorks, whose own creation in 1994 had rocked the Hollywood ecosystem, the company went big.

But like so many of DreamWorks’ star-reaching ventures, almost overnight, the risk proved enormous and the plan underbaked: Pop became one of the company’s most spectacular flops.

Quibi, which launched in April to underwhelming reviews, has much in common with its predecessor—including an obsession with boldfaced names. Katzenberg lured Silicon Valley veteran Meg Whitman to serve as CEO, appointed Condé Nast CEO Roger Lynch to Quibi’s board, and scooped up former Hollywood Reporter editor Janice Min, former DC Entertainment president Diane Nelson, and former Viacom executive Doug Herzog to help lead the content division. The talent he signed to produce Quibi shows reflects the same movie studio mentality: Spielberg, Jennifer Lopez, Chrissy Teigen, LeBron James, to name a few. (Min and Nelson have since departed the company.)

As with Pop, Quibi was preceded by a nonstop publicity storm—from appearances at every major business conference to Super Bowl ads—and heavy on show-stopping figures: $1.8 billion in backing from Hollywood studios and the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba; payments of up to $6 million an hour for TV shows; projections of seven million users in the first year and $250 million in subscriber revenue.

After its debut two months ago, where Quibi was the fourth-most popular app download in the United States, it tumbled to No. 1,413 on June 3, according to AppAnnie. It has since rebounded to No. 437, as of June 22, but it still faces other headwinds.

Earlier this month, The Wall Street Journal reported that Quibi is on track to sign up less than 2 million paying subscribers by year’s end (well short of its initial 7.4 million original target) and is burning through cash—the company says it will have spent $1 billion by the third quarter of 2020. Advertisers are disappointed; a promotional deal with T-Mobile was hurt when the mobile phone company closed stores due to the coronavirus; and a patent lawsuit is being lobbed by an interactive video company that’s backed by hedge-fund giant Elliott Management.

In an interview with Fast Company, Whitman says she remains bullish on Quibi’s future, despite a launch that was “a little slower than I’d like,” due to the pandemic, which has kept people from being on the go as much—and thus less in need of short-form content. She states that the app has been downloaded over 5 million times and that over 1.7 million people have signed up for the app via a free, 90-day trial. “I’m not unhappy,” Whitman says of Quibi’s first two months. “I’m quite pleased.”

She argues the company has been quick to respond to users’ demands, such as allowing the app to be streamed on TVs via Google Chromecast and Apple AirPlay—at launch, Quibi was only available on mobile devices. And she promises that more features are in the works.

As for comparisons between Quibi and Pop.com (which she was not involved with), Whitman says the landscape has changed: “When Pop launched, there were no mobile phones, no mobile apps. Online advertising didn’t exist. Certainly mobile advertising didn’t exist.”

Of course, Pop never really launched—which is one reason Quibi’s troubles are more pronounced. Still, the parallels are difficult to ignore, from Katzenberg’s drive to identify a white space in the media ecosystem to his penchant for throwing money at his problems.

Might an honest reckoning with Pop’s failure have saved Katzenberg from making the same mistakes twice?

Whenever Pop has come up, Katzenberg has been able to frame it as a visionary play—YouTube, five years before YouTube—without wrestling with the fundamental differences between the two. This time around, Katzenberg hasn’t had to wait five years for the tech-world rival that usurped his dream. He grew agitated last month when The New York Times made the comparison between Quibi and TikTok, the short-form, user-generated-video app that’s been thriving during the coronavirus. “That’s like comparing apples to submarines,” he said.

Whitman is less testy. Of the “incoming fire” that she and her colleagues have taken, she jokes: “Listen, it’s better than running for governor.” (Whitman lost California’s 2010 gubernatorial race to Jerry Brown.)

Hollywood’s leadership has always struggled to understand digital entertainment, but if Katzenberg hasn’t learned from his first failure to marry Hollywood with short-form digital video, perhaps others can. Ten years ago, I published a book on the history of DreamWorks, The Men Who Would Be King: Movies, Moguls and a Company Called DreamWorks. The following account of Pop.com’s spectacular rise and fall is adapted from that original reporting.

Dot-com mania was sweeping the nation. Twenty-six-year-olds were becoming insta-millionaires. It was perhaps inevitable that DreamWorks would want in. Here was an industry where money could be made overnight in an initial public offering, give or take a solid business plan, and that spoke directly to Spielberg’s inner geek. This was the guy, after all, who had a T-1 line way back when. When Netscape initiated the internet boom back in 1995, raising $2.2 billion its first day as a public company, Spielberg had brought in the press release announcing the news to the guys at DreamWorks Interactive, remarking how “cool” it was. Four years later, with the bubble wildly expanded and tech IPOs in headlines daily, DreamWorks wanted to move, as did many others in Hollywood.

It became “a bit of a land grab,” said David Bloom, reporting on the tech boom in L.A. for the publication Red Herring. “It was like the Oklahoma Sooners—oh my God, there’s free land, we have to grab it!”

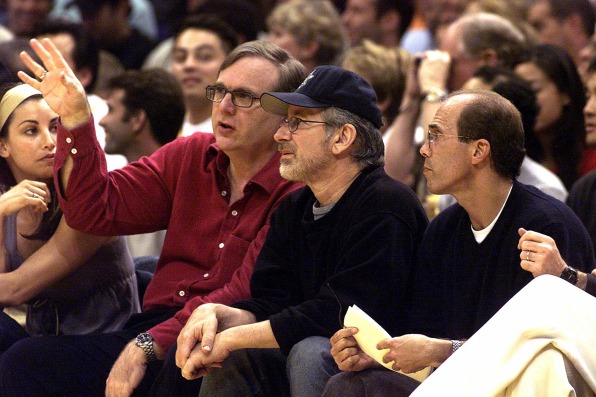

Enter DreamWorks with a proposal for an entertainment dot-com. See Paul Allen—Microsoft cofounder and DreamWorks’ $500 million backer—pledge $50 million for a 50% stake in what would become Pop.com.

Pop was actually the brainchild of Ron Howard, one of the biggest directors in Hollywood (Parenthood, Apollo 13) and one-half of one of the biggest production companies in Hollywood, Imagine Entertainment. The other half was Brian Grazer, a high-energy, spiky-haired surfer who prided himself in knowing everyone (an assistant cum cultural attaché rounded up names and forged introductions to people such as The Tipping Point author Malcolm Gladwell and Frank Wilczek, a Nobel-winning expert on particle accelerators). Grazer flipped when he heard tech geek Howard going on about using the web as a platform for inexpensive, experimental entertainment, or “pops”: short films, streaming video, performance art, etc.

When Spielberg, a longtime friend of Howard’s, heard about Pop, he flipped too. While Spielberg and Howard gushed ideas, Grazer and Katzenberg became designated implementers, despite the fact that they were far less web-savvy than their partners. (Katzenberg “searched” the internet by having his staff “record” web pages onto a videotape, which he then popped into a VCR. He replied to e-mails by fax. Grazer had to ask his assistants to pull up web pages for him. Underlings also printed out his e-mails so he could read them on paper.)

In October 1999, Pop.com was announced to enormous fanfare: A revolution was at hand. Grazer was flying all over, meeting with potential contributors and partners, such as Interview editor Ingrid Sischy, Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter, and artist Jeff Koons. And then there was the Imagine and DreamWorks’ Hollywood roster: Mike Myers, Steve Martin, Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, and so on. Katzenberg and Grazer went to all the agencies, pumping Pop, comparing the internet to what MTV had been 25 years earlier. Spielberg called it a “large, fertile field.”

“You can harvest all sorts of spinoffs, just from whatever germinates,” Spielberg said. “It could be a book, a piece of music, a movie—who can say?”

It was a good question.

Not anyone at DreamWorks, or anywhere else, for that matter, could necessarily define exactly what they were setting out to do. Or what limitations they were facing with a platform—the internet—that was not yet fully mature. Paul Allen’s prediction concerning full broadband access within a year was far from certain. Timing would matter quite a bit, considering that the types of content Pop would carry—streaming videos, short films—would require quick, uncomplicated access in order to download in a user-friendly manner. (Via dial-up, a short film might take eight hours to download.)

But tough questions weren’t part of the dot-com mentality. “All of these guys were ahead of their time, but most were not sufficiently concerned about a sustainable business model,” said reporter David Bloom.

In March of 2000, just months after America Online met Time Warner and wed to the tune of $200 billion, Pop.com held a launch event at the Chateau Marmont during the Yahoo! Internet Life Online Film Festival. The party was far more opulent than those of any of the other companies playing host at the Chateau. DreamWorks/Imagine rented out one of the fabled hotel’s biggest bungalows—more of a house, actually—and handed out fruity cocktails by the pool, along with “tchotchkes with striking graphics and uncertain utility,” said Bloom. Most impressive of all, the stars themselves showed up, or at least some of them—Howard, Grazer, and Katzenberg—who chatted with young Netheads hawking streaming shorts.

A new era was at hand. The Chateau, formerly ground zero for Hollywood bacchanalian behavior—Jim Morrison had leapt from the roof; Jim Belushi had overdosed here—was now playing host to squeaky cleans whose drugs of choice were venture capitalism and portfolios. As Red Bulls were passed around, DreamWorks executives gulped and then raised up the cans to toast another relatively “risk-free”—or at least entirely bankrolled—investment whose upside was the chance to make history.

What could possibly go wrong?

Very quickly, Pop.com would have been more aptly called Implode.com. By the spring of 2000—when Pop was supposed to launch—there was no actual website in sight. Nor was there any clear timetable for when engineering issues would be resolved. Or the building of hundreds of different web applications.

Not that this stopped anyone.

Practically overnight, there were 125 people on the Pop payroll, all of whom showed up for work every day in a Glendale warehouse that had housed early Shrek animators. Inside, on the stage, where the Propellerheads had once supervised motion-capture tests, couches and beanbag chairs were set up for gatherings. A piano and a Ping-Pong table were propped nearby. Lunch was delivered daily, and, on Friday afternoons, party food and beer were rolled in.

“Pop was a very busy place for a company without a website,” said Phillip Nakov, cofounder of CountingDown.com, a site bought by Pop. “Between production, design, writers writing things, people shooting things, making shows, editing shows, acquiring content . . . there was a lot of activity.” But Mike Kelly, founder of Undergroundfilm.com, which Pop was in the process of acquiring, was more dubious. “They had a lot of people working there,” he said. “Everybody had an assistant. I just couldn’t identify what they were doing.”

That was a mystery hard to penetrate. Pop’s CEO, Kenneth Wong, another Katzenberg hire from Disney, where he’d worked at Imagineering, had no experience in the internet and seemed clueless as to how to get Pop up and running. An architect with a background in construction management, Wong was accustomed to Disney’s rigid bureaucratic structures. He was hardly an entrepreneurial internet pioneer who thought in terms of overnight growth and profitability. Wong’s number two was another tech newbie: Dan Sullivan, a 27-year-old Wharton grad who had overseen business development at Imagine.

One Pop employee called Wong the “cheerleader in chief,” someone who was good at team spirit and talking the talk, but who had more trouble with the meat of it all. There were meetings, inspirational speeches, and bonding activities, but as for meaningful work getting done: not so much.

In the dot-com spirit, Pop’s compensation model was all about stock. The plan was to build the company quickly and then make millions, if not billions, in an IPO. Employees were paid in stock, as was the talent being wooed to make content, a model that was especially pleasing to the frugal Katzenberg.

The only problem was that there was so much stock—Pop was incorporated with 250 million shares—that it wasn’t ever likely to be worth very much.

“Having raised money and incorporated a company, I remember looking at the number of shares and thinking, Lord, that is an astronomical number,” said Kelly. “A lot of people probably thought they were getting a buck a share, that the company would go public, and they’d be selling for $40 a share. But if the hundreds of millions of shares are, when you go public, 10 shares to 1 or something, it’s sort of misleading, and I think that was the purpose—to mislead.”

Some balked. When the stock situation became clear, the deals with A-list talent, always a part of the plan, fizzled. (Pop had even established a star tier system, which broke down actors and filmmakers that Pop hoped to hire into A, B, and C lists. Each category was allocated different stock paydays. A-listers included Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy, Steve Martin, and Jim Carrey. Jerry Seinfeld was the B team. And MTV prankster Tom Green a hapless C-lister.) When this “list” was leaked via reporter Chris Petrikin at Inside.com, agents bristled. Pop was now a foe.

From the Pop point of view, it was agents who were “pigs at the trough,” said one source. “Everybody was in the roaring dot-com mindset, where any agent thought they had a viable name that could change the face of the web. Mike Myers’s agents asked for the most, and when Pop didn’t give it, they discouraged their client from doing work for Pop. (Not that he especially wanted to—Myers was already in an ugly feud with Imagine over the film Dieter, based on Myers’s black-turtleneck-clad, Teutonic, “Sprockets” character on Saturday Night Live.)

Grazer and Katzenberg, who had each been clocking as much as 30 hours a week on Pop, were by now smelling failure and started pulling back.

As for Spielberg and Howard, Pop’s biggest cheerleaders, they were being sucked back into directing projects. Spielberg was preparing to shoot A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, having put Minority Report on the back burner. Like so many things at DreamWorks whose creation was owed to Spielberg’s interest and enthusiasm—DreamWorks Interactive, TV animation, GameWorks, not to mention its Playa Vista headquarters—Pop was ultimately abandoned by the director when his ever-shifting attention was captured by something that looked like more of a winner.

Then the real bottom fell out: In April, the NASDAQ collapsed. The internet gold rush was over. Dot-coms had gone from bubble to burst. San Francisco, the bust’s epicenter, was being deserted by entrepreneurs turning out the lights and putting their names on the months-long U-Haul waiting list.

Suddenly, the prospect of Pop going public and making a gazillion dollars was as likely as Katzenberg turning into Steve Jobs.

Pop reacted with typical Hollywood denial. With Spielberg, Allen, and Geffen as protectors, Pop was immune. Right? “We were aware of the internet bubble bursting, but we felt we were insulated because we were a privately held company,” said Nakov. “We had [Paul Allen’s] Vulcan funding, [so] we felt we were insulated from everything going on in the rest of the world.”

The attitude at Pop could best be summed up by a contest that Wong, who always tried to maintain a certain campy cheer, organized to choose the company’s logo. In the spirit of Everyone’s Ideas Are Important Here, he sent around a memo, urging all to help determine the catchphrase that best defined the company.

The winner, by a landslide, was: “Nobody’s Bitch.”

When the internet bubble burst, that attitude kicked in: Screw you, we will survive! But outside the insulated walls of the Glendale warehouse, Pop was becoming a lightning rod for reporters hungry for the next dot-com bust story. Sensing something brewing or busting, Entertainment Weekly and Inside.com were among the news organizations taking a look.

In early August 2000, Ken Wong showed up at Pop and asked everyone in the company to gather round. Everyone expected another go-get-’em speech as they filed into the large open area in the warehouse-cum-office where such meetings were held.

What had inspired this particular conclave was a story in that morning’s L.A. Times. It was a particularly harsh look at Pop, stating that “nine months after five of Hollywood’s most powerful players combined to create an online entertainment site, Pop.com is foundering so badly that certain partners are seeking a graceful way out before it has aired a single show.”

Addressing bad press had become a sort of ritual at Pop, as it had occurred with more and more frequency since the internet bust, when Pop’s own fortunes began a relentless slide. By the summer of 2000, there was still no launch date in sight, and now, as the Times story rightly stated, DreamWorks and Imagine were looking for a graceful escape. Pop had been in talks to merge with the websites Atom Films and iFilm for months, the idea being that by acquiring already existing websites, Pop would be able to launch faster.

But now, the talks with those companies were more urgent, and they were less about building up Pop than letting it go. A “merge” would be a way for DreamWorks and Imagine to exit a company that had burned through $7 million in startup cash with virtually nothing to show for it. By now, even Paul Allen was asking questions.

The sense within the company was that the media was playing hardball because it was SKG (Spielberg, Katzenberg, and Geffen), and there was an element out there that wanted the mighty moguls to fall. “Along the way there’d be stories that came out that didn’t really have much to do with anything,” Phillip Nakov said. “I almost feel—I know this from personal experience in this business—that everyone was just holding their breath for [Pop] to fail.”

But on that early-August morning, Wong didn’t launch into an explanation or analysis of the doomsday Times story. He responded to it, rather, by hanging up a piñata, taping the name of the reporter, Greg Miller, who’d written the story, and proceeding to smash it to a papery pulp.

Then he let others take a whack.

Oddly, Wong didn’t seem visibly upset. It truly did feel more like a game, an almost Scientological exercise in excising, or at least denying, the reality imposed by the outside world. “It was like a high school pep rally that was oblivious to the reality of the situation,” said one former Pop employee. “It was like the violinist performing on the deck of the Titanic going down.”

And the ship was, most certainly, sinking. By the end of the month, the plug was pulled on Pop for good, proving that no amount of wishful thinking, nor the protective power of SKG, none even Paul Allen’s millions, could keep the enterprise afloat.

Nakov, who would retain his connection to DreamWorks via CountingDown.com—which became DreamWorks’ online presence—received the news over Labor Day weekend. “I got the call at 9:30 in the morning on Saturday from Jeffrey,” he said. “He called to let us know there was going to be an announcement made the following Tuesday that Pop was not going to launch. He wanted to give us a heads-up that we [CountingDown.com] were going to be kept around.”

After the announcement by Katzenberg, “Most people were in shock,” said Nakov. “I just remember being very nervous; I think I went out for a smoke.” Soon madness settled in. Executives began running around, ripping up contracts so that artists and filmmakers would be able to take their projects elsewhere and not have it in writing that their rights were owned by Pop.

If the media had been hounding Pop in the weeks and months leading up to its fizzle, when it really did go under, the press went haywire, zeroing in like buzzards on a carcass.

Another bold misfire from SKG. This was news.

But despite all the bluster, Pop was one of the more minor internet disaster stories, having lost just $7 million, in comparison to the tens, and in some cases hundreds, of millions of dollars lost by the multitudes of dot-coms caught in the technology bust. Pop’s loss was a drop in the bucket compared to, say, the $60 million that was soaked up by the Digital Entertainment Network, a high-profile Hollywood dot-com that produced a few dozen online TV episodes before it went belly-up.

As for Paul Allen, the cost of Pop was nothing compared to the $250 million he lost on the Interval Research Corporation, which he had finally shut down months before. And both DreamWorks and Imagine had certainly seen more disastrous results just from a single movie that bombed.

More than anything, Pop was a symbolic failure. Its trajectory—what went right, what went wrong—contained elements of so many DreamWorks endeavors. There was the hype, the hubris of a new, never-before-seen entity. There was the star power of not just SKG but Imagine. There was the initial, though not lasting, enthusiasm of Steven Spielberg. There was the sweat and toil of Katzenberg. There was the remove of Geffen—and Allen, who yet again ponied up the funds. There was the absence of any real business plan or truly experienced people selected on the basis of something other than a prior history with Disney. There was money that was freely spent. There was the untimely shift in the market; the belief that the broadband revolution was right around the corner.

At the same time, it can’t be denied that Pop was ahead of its time, as would become clear when, years later, the video-sharing website YouTube became one of the hottest websites in the world. Allen’s prediction that by 2000 the world would be interconnected via high-speed internet was off by a few critical years. But the essence of his idea was correct. Once again, DreamWorks had trouble synchronizing the dream and the reality.